The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Complete Series from Letters to the Housed by Paul Asplund of SecondGrace.LA

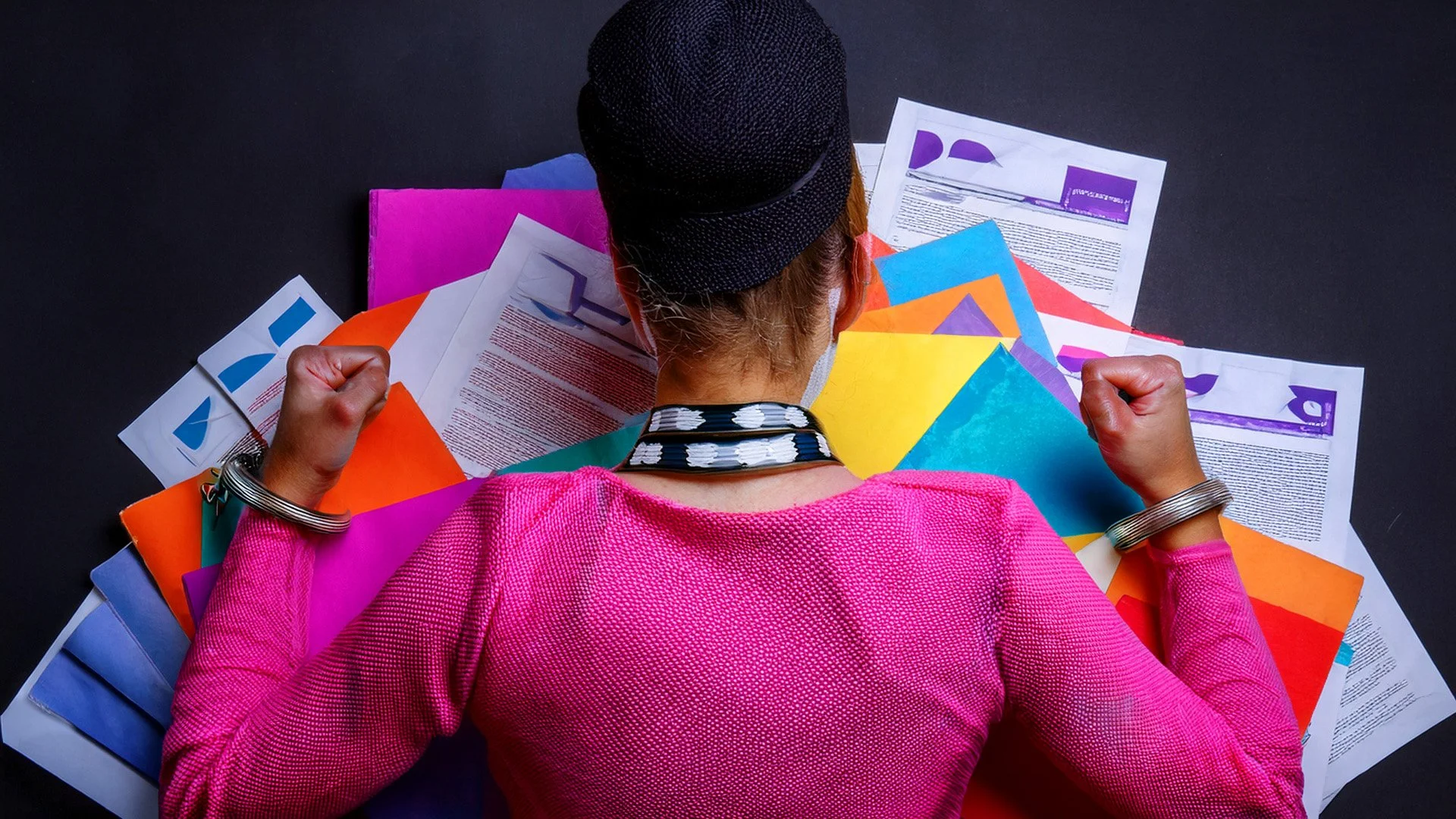

The weight of compliance. How funder expectations warp mission-driven work. Illustration by Delux Multimedia.

How the Nonprofit Industrial Complex Warps Mission-Driven Work

The complete three-part series on institutional isomorphism, the starvation cycle, and my experience at Lava Mae.

This compilation brings together the complete "Revolution Will Not Be Funded" series, originally published in November 2025. For those who missed a part—or want the full picture in one place—here's everything: from the academic framework explaining why nonprofits drift from their missions, to the funding mechanisms that starve them, to my personal story of watching it happen at Lava Mae.

Part 1: When Growth Means Losing Your Way

Originally published November 11, 2025

I found myself having this conversation again last week, for the umpteenth time, about how we resolve the tension between the needs of the people we serve and the funders (who we also serve).

It's a conversation every nonprofit leader knows by heart. You've got innovative ideas that work on the streets, in the communities, with the people. Your programs are designed for the people you serve. Your team is passionate. Your impact is measurable and real. You've raised a little bit of money from friends, family, and small funders who believe in your leadership. And then the big funders start paying attention.

At first, it feels like validation. Someone with life-changing resources sees what you're doing and wants to help you do more of it. But that "help" often comes with strings—lots of them. There will be quarterly reports with specific metrics. Your overhead ratio will be challenged and your budget rewritten to their specifications. They'll want board members with business backgrounds. They'll want you to replace the passionate friends and supporters who've been with you from the start with "C-suite" types. They want a strategic plan that looks like something McKinsey would produce.

They want you to transform from impassioned leader to CEO.

And slowly, imperceptibly at first, you realize you're no longer building the organization that serves your community best. You're building the organization that funders recognize and trust.

I've seen it happen over and over, as a nonprofit grows more successful, and the funders start to pay attention, the lure of funding warps the mission of the nonprofit. The funding becomes a burden that requires the nonprofit to divide itself into two discrete parts: the "C-suite" and the programs. It's a variation of the corporate takeover of all social movements that Chris Hedges details in his 2010 book, The Death of the Liberal Class.

I watched Lava Mae, once a darling of innovation, compassion, and human-centered design, slowly buckle under the weight of funder expectations. We refused to take money with encumbrances, and that refusal made us untenable in the long run. Corporate funders wanted marketing opportunities. Private funders wanted impact measured in KPIs that served their needs, not the needs of people on the streets.

There have been many books and articles written about this problem, and as many solutions proposed. Few have succeeded because funders tend to prefer a corporate structure to manage their contributions.

This requires the nonprofit to hire an administrative layer, and the mission splits. The part you care about is service, the part that will take all of your time is administration.

Since the demise of Lava Mae and in the nonprofits where I've worked since, I've spent time looking at solutions from alternative for-profit business models. Books like Rework by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson, and studies on holacratic approaches that create "flat" organizations. None solved the core problem: big money—the kind that makes or breaks programs—looks for its own kind. Academic credentials. College educated. Business minded. Privileged. Funders rarely see value in lived experience and people-first solutions.

This is the impossible bargain: grow successful enough to attract resources, then watch those resources warp everything you built.

The Iron Cage

In 1983, sociologists Paul DiMaggio and Walter Powell published a framework that explains exactly how this happens. They called it "institutional isomorphism"—the process by which organizations in the same field become increasingly similar to each other over time.

And they identified three mechanisms:

Coercive isomorphism: Formal and informal pressures from funders, government agencies, and regulators which force organizations to adopt certain structures and practices.

Mimetic isomorphism: When starting from scratch, organizations imitate other successful organizations in their field, assuming those structures must be what works.

Normative isomorphism: The expectation that leaders have MBAs, that boards include business executives, that strategic plans follow corporate formats.

Their devastating insight remains relevant four decades later: "Bureaucratization and other forms of organizational change occur as the result of processes that make organizations more similar without necessarily making them more efficient."

Again. Organizations become more similar without becoming more efficient. They start looking alike without actually working better.

A 2021 study of Swiss nonprofits found that coercive pressure from funders without providing internal organizational strategies leads directly to mission drift.

2011 research on UK charities showed how government contracting results in organizations "operating well outside their original missions." Three of the charities they studied accepted mission drift as "a fact of life" rather than a problem to resist. When your survival depends on government contracts, and those contracts require you to provide services outside your expertise, you drift.

You have to.

The pattern is consistent: nonprofits compete for social legitimacy and funding, forcing them to adopt structures and practices that funders recognize and trust—even when these structures undermine their distinctive mission-driven characteristics.

A 2014 study documented how activist organizations increasingly look and act like multinational corporations, with narrow thinking, bureaucratic structures, and fundraising priorities that lead them to treat people as donors rather than empowering them as changemakers.

Consider Greenpeace. It evolved from what they called a "motley band" of environmental activists into an Amsterdam-based multinational with thousands of employees managing a multimillion-dollar brand. Or the Susan G. Komen Foundation, whose annual fundraising and education costs exceed $200 million—higher than the GDP of the Marshall Islands—yet operates with corporate efficiency metrics that prioritize scale over impact on actual breast cancer outcomes.

This is what success looks like in the current system: become a corporation that happens to have a charitable mission, rather than a mission-driven organization that needs resources.

The Nonprofit Industrial Complex

The INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence collective gave this a name most of you will recognize: the "nonprofit industrial complex" (NPIC). In their 2007 anthology The Revolution Will Not Be Funded, they define it as:

"A system of relationships between the State, local or federal governments, the owning classes, foundations, and non-profit/NGO social service & social justice organizations that results in the surveillance, control, derailment, and everyday management of political movements."

INCITE! experienced this directly. In 2004, the Ford Foundation offered them a $100,000 grant. Then they rescinded it because INCITE! supported Palestinian liberation. The message was clear: certain politics are fundable, others are not. And funders decide which is which.

Dylan Rodriguez, contributing to the anthology, argues that the NPIC represents a "White Reconstructionist agenda" that criminalizes radical dissent while philanthropic institutions facilitate state violence under the guise of benevolence. The nonprofit form domesticates radical politics into manageable, fundable activities.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore describes nonprofits as operating as a "shadow state"—taking over functions previously performed by government while allowing the state to shirk responsibilities yet maintain control through funding mechanisms.

Robert L. Allen's historical analysis revealed how Rockefeller, Ford, and Mellon foundations facilitated violent state repression of radical Black liberation movements in the late 1960s-70s by funding moderate elements. They didn't need to directly oppose radical organizing; they just needed to make moderate approaches well-funded and radical approaches financially impossible. The movements split. The power diffused.

We read about this every day: universities, corporations, people held hostage, sometimes literally, with terms like DEI and 'woke' suddenly out of favor and dangerous to support. Obeisance to power is compulsory.

Vu Le, founder of Rainier Valley Corps and author of the influential Nonprofit AF blog, describes how "we always make sure that program officers are feeling good, that they like us, because otherwise we could jeopardize funding for our organizations." He coined the term "funder fragility" to describe how funders get offended when criticized, diverting conversation from real issues while the power imbalances teach nonprofits to be afraid to be honest.

He describes a gathering of nonprofit professionals of color that was derailed when a foundation officer took offense to complaints about philanthropy. The entire conversation shifted to managing the funder's feelings rather than addressing systemic problems. This is how power works: the least vulnerable people require the most protection.

Edgar Villanueva spent 14 years working inside philanthropic institutions. An enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe, he witnessed what he calls "old boy networks, the savior complexes, and the internalized oppression among the 'house slaves'" while philanthropy sits on $800 billion of assets. Yet only 7-8% goes to communities of color—meaning communities are "stolen from twice."

His observation cuts to the heart of it: "All of us who have been forced to the margins are the very ones who harbor the best solutions." But those solutions remain unfunded because funders with the least connection to problems control resources meant to solve them.

Part 2: Funders Prefer Their Own Kind

Originally published November 18, 2025

We ended Part 1 with a quote from Lumbee Tribal member Edgar Villanueva. "All of us who have been forced to the margins are the very ones who harbor the best solutions." But those solutions remain unfunded because funders with the least connection to problems control resources meant to solve them.

This week, we're going to dig a little deeper into the inequality, and inequity, in the vast majority of nonprofit boards.

A 2021 analysis of major nonprofit boards—Feeding America, Habitat for Humanity, the Gates Foundation, and the Red Cross—found that finding a board member without a prestigious university degree is "an anomaly." Many board members also serve as executives for other companies, creating a class barrier between aid givers and recipients that "reduces the autonomy of the working class and fosters a lack of understanding between providers and beneficiaries."

Nonprofit Quarterly reported in 2022 that 9.5 out of 10 philanthropic organizations are led by white people. Only 7% of nonprofit chief executives and 18% of nonprofit employees are people of color. And among the largest nonprofits, almost 90% of the leadership roles are occupied by white people.

The financial disparities are stark. Black-led organizations are 24% smaller in revenue than their white-led counterparts and have unrestricted net assets that are 76% smaller. This reflects systematic underfunding of organizations led by people closest to the problems and reveals deeply embedded values about who is trustworthy and competent.

The barrier is access and opportunity, not interest or ambition.

Myrl Beam, author of Gay, Inc., observed that as the gay rights movement became reliant on wealthy donors and philanthropy, "the goals of the movement began to shift to be more in line with what those funders would prioritize. So, why [gay] marriage? Because rich people wanted it."

The movement's priorities aligned with the interests of wealthy funders rather than the most vulnerable LGBTQ+ community members who might have prioritized housing, employment discrimination, or healthcare access. Marriage equality is important. But it became the priority because funders could relate to it personally.

This is how mission drift happens: not through malice, but through proximity. Funders fund what they understand, what they can measure, what looks like the solutions they would design. And if you want their money, you have to become what they recognize.

The Starvation Cycle

Ann Goggins Gregory and Don Howard's 2009 Stanford Social Innovation Review article "The Nonprofit Starvation Cycle" documented a four-stage vicious pattern that systematically starves nonprofits of necessary infrastructure.

Stage One: Unrealistic Expectations

Government contracts and private Foundations typically allow only 10-15% for indirect expenses. A Better Business Bureau surveys show over half of American adults believe nonprofit overhead should be 20% or less.

Yet for-profit service industries report average overhead rates of 25%, with none below 20%.

Nonprofits are expected to operate at overhead levels that no successful for-profit company would dream of. We're supposed to compete for talent, maintain technology, ensure compliance, and produce extensive reporting—all while spending 10 percentage points less on infrastructure than businesses that don't have to produce any of that reporting.

Stage Two: Pressure to Conform

The Urban Institute's Nonprofit Overhead Cost Study found that 36% of nonprofits felt pressure from government agencies, 30% from donors, and 24% from foundations to keep overhead artificially low.

One organization in their study spent 31% of a grant's value just administering it—while the funder specified only 13% for indirect costs. The organization had to subsidize the funder's unrealistic expectations from other sources.

It forces nonprofits to engage in 'cost-shifting' and while funders get to look good by claiming low overhead, nonprofits scramble to find other money to cover the real costs of doing the work.

Stage Three: "Low Pay, Make Do, and Do Without"

Many organizations studied had nonfunctioning computers that couldn't track program outcomes, and their staffs lacked necessary training.

One staff member spent 50% of her time manually typing data into an outdated Access database (I've done as much myself).

This means the people who should be working directly with homeless individuals, or teaching kids, or providing healthcare, are instead hunched over computers entering data by hand because funders won't pay for the databases that would automate this work.

And then those same funders ask for detailed impact reports generated from that data.

Stage Four: Misleading Reporting

An analysis of 220,000+ IRS Form 990s found that more than one-third of the organizations reported NO fundraising costs. One in eight reported NO management and general expenses. These are statistical impossibilities leading to systematic misreporting.

A Chronicle of Philanthropy survey confirmed that accountants advised nonprofits to report zero in fundraising sections. Not because fundraising was free, but because reporting real costs would hurt their chances of receiving future funding.

The actual overhead rates for four studied youth-serving organizations ranged from 17-35%, yet they reported 13-22% on their 990s.

We choose to lie because telling the truth is punished. And lying just reinforces the unrealistic expectations.

Here's what some funders don't understand: every hour we spend managing your restrictions is an hour we're not spending on the mission you claim to support. You're stealing time from the people we serve.

When you fund programs but not infrastructure, you're building houses without foundations and then acting surprised when they fall down.

Dan Pallotta's Cautionary Tale

I remember when this story broke. I was living in San Francisco and a close friend of mine was an executive working on the AIDSRide. Dozens of our friends rode every year. The AIDS ride is almost a sacred institution for our community. It's been known to changes lives, not just through the programs it funds but for the riders themselves. When the story broke, the sense of betrayal and misunderstanding was universal, and seemingly misplaced.

The papers told us to be outraged and we were. It wasn't until years later that I learned what really happened.

Pallotta TeamWorks created the AIDSRides and Breast Cancer 3-Days events. Over 9 years, they raised $236 million for HIV/AIDS. And over 5 years, they raised $333 million for breast cancer. These were among the most successful charity fundraising events in history.

To build that capacity, they spent 40% on overhead. They invested in professional marketing. They hired talented people and paid them competitively. They built infrastructure to scale. And when the press discovered the 40% overhead rate, sponsors pulled out and the events shut down.

Two of the world's most successful charity events were eliminated. Thousands of beneficiaries were harmed. And $569 million in future fundraising capacity was destroyed.

Dan Pallotta didn't fail at fundraising. He was immensely successful at it. He failed at meeting an arbitrary overhead ratio that no one can actually link to effectiveness. This "overhead apartheid," as he called it, judges nonprofits by different standards than for-profits and pushes talented people from the nonprofit sector into for-profit work because they can't afford to live.

The impact of "overhead apartheid" looks like this: since 1970, only 144 nonprofits have crossed the $50 million annual revenue threshold. In the same period, 46,136 for-profits did. A ratio of nearly 9:2,900. Yet as of 2023, Pallotta notes the overhead myth persists in public consciousness—"the average member of the general public still thinks you ask about overhead."

If you invest in capacity, you will be punished.

Part 3: When Great Ideas Die from Exhaustion

Originally published November 25, 2025

In 2014, I was asked to join the Advisory Board of Lava Mae as their first member with 'lived experience.' As I've said before, I hid my experience for years out of shame and I had no idea that my experience was valuable to anyone. After a few months of working alongside our teams on the streets, I took on the first operations role and held various program roles until I left in 2019. This story is deeply personal to me. The values and practices I bring to my work now, I learned from Lava Mae.

Lava Mae was everything funders say they want: innovative, scalable, human-centered, measurably effective. Founded in 2013, we provided mobile showers and toilets for unhoused people in San Francisco. We pioneered the concept of "Radical Hospitality," offering an unexpected level of service to our guests, an approach that won us praise around the world and birthed a movement which still exists today.

Our impact was remarkable:

We provided over 75,000 showers

We served over 30,000 unhoused neighbors

We hit our 5-year goal 16 months early

We expanded to Oakland and Los Angeles (and I moved to LA)

We received a $1 million grant from the San Francisco Foundation in 2018

And, we inspired 80+ mobile hygiene services worldwide

By every measure funders claim to care about, Lava Mae was a massive success.

But Lava Mae didn't survive.

In 2019, they dramatically scaled back operations:

From 6 trailers to 2

From multiple service locations to just Tuesday mornings outside the Main Library

From 22 staff to 11

From serving 12,000 people annually to 8,000

And LA operations were shut down

Doniece's explanation was stark: "For the first three years, I was working 100 hours a week... When you're working with vulnerable populations, the stress and the responsibility increases 100-fold... I'm pretty exhausted and needing some self-care."

When they told me we were shutting LA down I was gutted. My hours were cut, eventually I left.

After they shut down street operations, Lava Mae became the nonprofit accelerator known as Lava Mae X. They didn't last long after that.

No amount of innovation overcomes systematic underfunding of infrastructure and leadership sustainability.

But we had made a huge impact in the small corner of the nonprofit world where we worked. Lava Mae received 4,250 inquiries from cities, nonprofits, and refugee organizations globally. At least 80 launched as shower services and many still exist today.

Lava Mae made the conscious choice to avoid government contracts. It worked for us in the beginning, but when foundation funders went looking for other new projects, we were left behind. We may have died a quick death, but we avoided the slow death and mission drift I've seen so many of our peers experience.

We kept our mission and programs intact and avoided the slow strangulation of government contracts.

The Government Contract Trap

The National Council of Nonprofits research reveals systematic underfunding through government contracts. Among nonprofits reporting government caps on indirect cost reimbursement, 25% receive ZERO reimbursement for overhead. This means government is systematically underpaying by 15-25 percentage points.

Additionally:

72% report government requirements are complex and time-consuming

45% experienced late payments

State governments owed an average of $200,458 per nonprofit

Federal government owed $108,500

Local government owed $84,899

44% experienced mid-stream contract changes including cuts to payments or redefined expectations

For most nonprofits, being routinely paid 6-9 months late, paid you less than cost, and having the contract terms changed halfway through, would be fatal. That's the government contracting environment for nonprofits. And it's getting worse under the current administration.

An Urban Institute survey from April-June 2025 found:

One-third of nonprofits experienced government funding disruption

21% lost a grant or contract

27% faced delays or funding freezes

6% hit with stop-work orders

As a result:

29% reduced staff

21% were already serving fewer people

Despite need remaining constant or increasing. This is a sector constantly on the brink of collapse.

The Measurement Problem

One survey found that while 76% of nonprofit executives said impact measurement was a top priority, only 29% thought they were "very effective at demonstrating outcomes." The problem with impact measurement isn't measurement itself. It's who controls what gets measured and why.

We default to measuring easily quantifiable inputs and outputs: dollars raised, people served, overhead costs. Not meaningful outcomes.

This creates multiple distortions:

First: Organizations avoid serving the hardest-to-reach populations because success metrics are more difficult. They want to keep the dollars flowing and if you work with people experiencing chronic homelessness with complex mental health issues, your "housing placement rate" will be lower than an organization that works with recently homeless families. So you cherry-pick easier cases to show better outcomes.

Second: The focus on quantity over quality means "number served" metrics don't capture depth of impact. One children's charity wanted to raise fees to provide better quality services, but the charitable side resisted because it would mean serving fewer people—and funders measure number served.

Third: Short-term grant cycles force focus on immediate measurable results. Preventive work that prevents problems years in the future gets undervalued because impact is harder to measure within typical 12-18 month grant timeframes.

And research on mission drift shows how metrics cause organizational distortion. A 2021 study found nonprofit social enterprises use strategies including:

"Structured ignorance" – deliberately not measuring certain things

"Problem reframing" – changing how success is defined

"Defensible trade-offs" – making mission compromises they can justify

Research shows organizations expand, distort, or shift services to be competitive for funding. Mission drift driven by resource dependency.

We're not measuring what matters. We're measuring what's measurable. And then we're distorting our missions to optimize for those measurements.

So, What Do We Do?

Funders say they want innovation, but punish investment in capacity. They say they trust us, but require surveillance-level reporting. They say they want impact, but won't pay for the infrastructure that produces it. They say they value lived experience, but their boards are filled with Ivy League MBAs. They say they want to solve social problems, but their restrictions guarantee we can't. And when great organizations like Lava Mae scale back because their founders are exhausted, or when visionaries like Dan Pallotta are destroyed for investing in capacity, funders express surprise and concern.

But they don't change the rules that created the outcome.

The evidence is overwhelming: as nonprofits grow and attract funder attention, the funding itself warps the mission. Not through malice. Through mechanisms that are well-understood, well-documented, and completely predictable.

Funders force us to look like corporations. The starvation cycle prevents infrastructure investment and funder-determined metrics distort priorities. And the power imbalances silence our voices.

But I know there are alternatives. I know organizations that have resisted these pressures for decades. I keep hearing about funding models that strengthen rather than weaken our missions.

The question isn't whether another way is possible. The question is whether those with power will choose it.

Additional Resources

Key Research Studies

Institutional Isomorphism

Mission Drift

Understanding and combating mission drift in social enterprises

Surviving mission drift: UK charities and government contracts

The Nonprofit Industrial Complex

The Nonprofit Starvation Cycle

The Overhead Myth

Dan Pallotta: The way we think about charity is dead wrong (TED Talk)

BBB, Charity Navigator, and GuideStar: Dispelling the Overhead Myth

Government Contracts and Nonprofits

National Council of Nonprofits: Common Problems in Government Grants and Contracts

Urban Institute: How Government Funding Disruptions Affected Nonprofits in Early 2025

Trust-Based Philanthropy

Lava Mae

Connect With Second Grace LA

Subscribe: SecondGrace.LA on Substack

Watch: Second Grace LA on YouTube

Support: Donate to Second Grace LA

All Links: linktr.ee/secondgracela

We're building a movement, not just an audience. If this series resonated with you, share it with someone who needs to read it.